Michelangelo

Buonarroti

1475-1564

Pieta

St. Peter's, Rome 1500

Unlike Leonardo, Michelangelo

was of noble birth. His father, Ludovico di Buonarotti, sent his son to

be raised by a stone carver and his wife, since his mother was too ill to

nurse him. It was because of this arrangement that the young boy learned

to carve. Michelangelo later wrote, "When I told my father that I wished

to be an artist, he flew into a rage, saying that 'artists are laborers,

no better than shoemakers.' " His father wanted him to be a man of letters,

a scholar of higher learning. When Michelangelo finally convinced him to

allow him to apprentice to be an artist, his talent emerged in very little

time. He went on to study at the sculpture school in the Medici gardens,

and when Lorenzo de Medici recognized his talent, was invited live in the

Medici household. In this environment, he was introduced to the great humanist

thinkers of the day, who were frequent visitors to the Medici court. He

would soon travel to Rome, witnessing the great marble statues that would

have a lasting impact on his art.

One of first

sculptures Michelangelo created upon his return from Rome was the Pieta.

It is one of his most famous works, finished before Michelangelo was

25 years old. The youthful Mary is shown seated majestically, holding

the dead Christ across her lap, a theme borrowed from northern European

art (see Gothic Pieta at right, circa early 14th century).

Instead of revealing extreme grief, Michelangelo's Mary is restrained,

and her expression is one of resignation. The theme was a compositional

challenge, as previous versions of the same subject always looked awkward,

with the dead Jesus practically falling off of Mary's lap. Michelangelo

adjusted the composition by enlarging Mary's figure. We fail to notice

her size because we are distracted by the folds in her drapery, the

realistic portrayal of flesh and muscles, and its harmonious composition. |

|

Just days after it was placed

in Saint Peter's, Michelangelo overheard a visitor remark that the work

was done by another artist. That night Michelangelo sneaked into the Cathedral

and carved an inscription on the sash running across Mary's chestin: "Michelangelus

Bonarotis Florent Facibat" (Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine, made

this). This is the only work that Michelangelo ever signed. He later regretted

his passionate outburst of pride and determined to never again sign a work

of his hands.

See Details of Pieta

David:

Symbol for the

Liberty of Florence

Having secured his reputation

as one of Florence's greatest sculptors, Michelangelo won another commission

for an important project. The statue of David was meant to commemorate the

liberty of Florence, a republic which had recently won its independence. The

biblical youth who slays a giant becomes a symbol for their this liberty, demonstrating that inner

spiritual strength can prove to be more effective than arms. Unlike Donatello's earlier version of the same subject, Michelangelo's David

is pictured before the fight, gazing into the distance at his opponent. Since

Goliath is not present, the story can be perceived in David's intense gaze,

as well as in his powerful hands. His left hand holds a slingshot, and his

right holds a rock. Carved

from an 18 ft. tall block of marble which had been abandoned by an earlier

sculptor, the finished size is over 14 feet tall. David is represented as an athletic, manly character, very concentrated and

ready to fight. Though his body appears to be relaxed (emulating the contrapposto

pose of classical Greek sculpture), the tension of the conflict is evident

in his worried look. In his writings, Michelangelo describes his warrior-hero:

"Eyes watchful...the neck of a bull...hands of a killer...the body, a

reservoir of energy. He stands poised to strike."

.

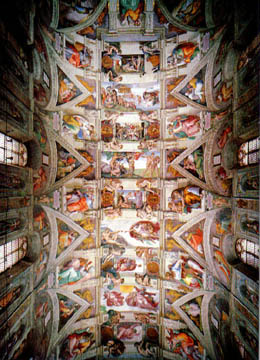

The

Sistine Chapel Ceiling

The Vatican, Rome (1508-1512)

An Overview of the Ceiling

|

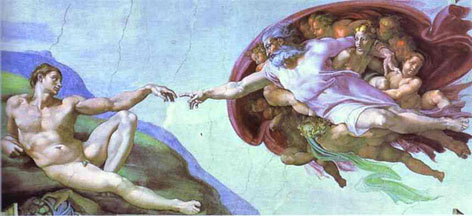

The Creation of Adam

By far the most

famous section of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling, Michelangelo depicts

Adam in his full physical form. The act of creation is in the touch

of the Creator's hand with that of Adam's. Behind God is the image

of Eve, as yet unborn, and other figures representing their descendents.

The child, which God touches with his other hand, probably refers

to the later birth of Christ.

|

Michelangelo was

commissioned by Pope Julius II to repaint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

after removing him from another project which Michelangelo was concentrated

upon finishing, that of Pope Julius' tomb. At first, Buonarroti tried to turn

down the commission, stating that he was a sculptor and not a painter. The

pope, however, was insistent. Despite his initial reluctance, the sculptor's

plans far exceeded the original order of 12 painted figures on the 44 x 128

foot ceiling. When he finished the painting four years later, he had painted

over 300 figures. Working high above the chapel floor, on scaffolding, these

are some of the greatest images of all time. On the vault of the papal chapel,

he devised an intricate system of decoration that included nine scenes from

the Book of Genesis, beginning with God Separating Light from Darkness and

including the Creation of Adam and Eve, the Temptation and Fall of Adam and

Eve, and the Flood. These centrally located narratives are surrounded by alternating

images of prophets and sibyls on marble thrones, other Old Testament subjects,

and by the ancestors of Christ.

The Creation of Eve

|

The Temptation and Expulsion

From Garden of Eden

|

Though the Creation of Adam is the most famous frieze from the Sistine ceiling, Michelangelo placed

the Creation of Eve at the exact center of the composition. The photo

at left was taken before the restoration of the ceiling. The Temptation and The Fall were in a similar state, with cracked plaster and colors

darkened by over 400 years of candle soot, until the frescos were recently

restored in the 1980s.

Michelangelo sketched all of

the images before the project of painting was begun. Some of these he altered.

Such is the case with the Libyan Sybil (a sybil is a female prophet,

or seer). The original cartoon shows that he studied the pose from a male

figure, but he decided to transform him into a female. This practice accounts

for the extremely muscular physique of his portrayal of women in general.

The photo at right shows a restorer working on this section of the painting.

One thing that is not evident in the central photo is the curved surface

on which it is painted. Michelangelo's mastery of perspective and forshortening

allows the viewer to see the figure at a distance without the distortion

that a lesser painter would have achieved.

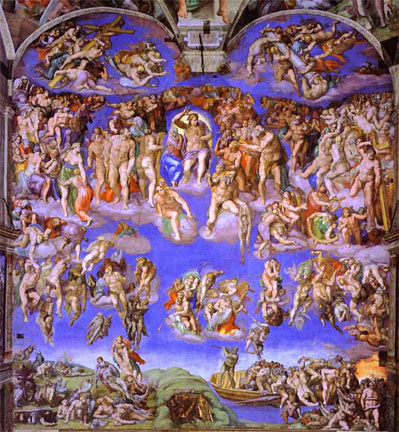

The

Last Judgement

Central Theme of the Last Judgement

(Sistine Chapel Altar Wall)

Created 25 years after the ceiling,

the Last Judgement was painted on the altar wall of the Sistine chapel.

The face of religion has changed with the intervening years. With the Reformation

of the Church, the attitude of the imagery is more severe than that which

is depicted on the ceiling. With a clap of thunder, God puts into motion the

inevitable separation, with the saved ascending on the left side of the painting

and the damned descending on the right into hell. Michelangelo portrayed all

the figures nude, but prudish draperies were added by another artist a decade

later, as the cultural climate became more conservative. Even before its official

unveiling, the Judgment became the target of violent criticisms of

a moral character. Biagio da Cesena, the Vatican's master of Ceremonies, said

that "it was mostly disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have

been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully",

and that it was "no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public

baths and taverns." Michelangelo's revenge was to paint Biagio in hell, in

the figure of Minos, with a great serpent curled around his legs, among a

heap of devils. (He was no less kind to himself, however, for Michelangelo

painted his own image in the flayed skin of St. Bartholomew). Others accused

the painter of heresy. One official of the church even called for the fresco's

destruction, and a long statement of charges was drawn up against Michelangelo.

But the nudity of the figures didn't bother Pope Paul III nor his successor

Julius III. It was not until January 1564, and therefore about a month before

Michelangelo's death, that the assembly of the Council of Trent took the decision

to "amend" the fresco by adding draped cloth around the offending parts.

Detail of Baggio,

a critic of the mural

|

St. Bartholomew's Flayed Skin,

at right,

St. Bartholomew's Flayed Skin,

at right,

is possibly a self-portrait |

One of the "Damned",

also self-portrait?

|

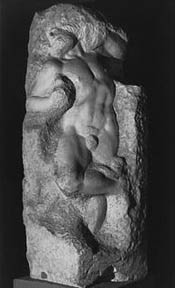

The

Tomb of Pope Julius

Dying Slave

|

Moses

|

Captive Slave

|

Before the assignment of the Sistine Ceiling in 1505, Michelangelo had

been commissioned by Julius II to produce his tomb, which was to include

more than 40 figures. Due to a mounting shortage of money, however, the

pope ordered him to put aside the tomb project in favor of painting the

Sistine ceiling. When Michelangelo went back to work on the tomb, he redesigned

it on a much more modest scale. Nevertheless, Michelangelo made some of

his finest sculpture for the Julius Tomb, including Moses (c. 1515),

the central figure in the much-reduced monument now located in Rome's

church of San Pietro in Vincoli. The muscular patriarch sits alertly in

a shallow niche, holding the tablets of the Ten Commandments, his long

beard entwined in his powerful hands. He looks off into the distance as

if communicating with God. (Michelangelo's Moses has horns because

one of the biblical translations of "rays of light" became "horns" in

Italian. Because of this mistranslation, depictions of Moses with horns

has become somewhat commonplace.)

Two other statues that were

meant to hold up the pope's tomb are the Bound Slave and the Dying

Slave (c. 1510-13). Both are considered to be unfinished, but the Captive Slave, in particular, demonstrates Michelangelo's

approach to carving. Michelangelo often referred to the process of carving

as one in which he discovers the form which is already imprisoned in the

stone. He believed that his job was to release what was already there.

It is also his belief that the human soul is a prisoner who strives to

be released from its bodily form. This, I feel, is the true message of

the Captive Slave.

| Michelangelo

lived to a ripe old age of 89 years, and continued to work almost

to the last day. In addition to many paintings and sculptures

not cited on this page, he is also known for his achievements

as an architect and a poet (both which he was notably talented

at). Despite a life of super-human achievements, he was disappointed

at himself for not achieving more. The writings of his later years

reveals a sad genius, convinced that he was at the height of his

creative powers just as his physical powers were decreasing. |

|

|

to Raphael

|